Case

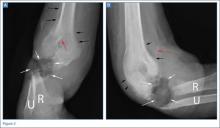

A 32-year-old woman presented to the ED with a 6-month history of worsening skin erosion along her right elbow and forearm. The patient described unremitting pain and progressive shortening of her forearm. Radiographs were obtained; representative images are shown above (Figures 1a and 1b).

What is the diagnosis?

***BREAKING***

Answer

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the right elbow demonstrated a large soft tissue defect involving the proximal forearm (white arrows, Figures 2a and 2b) with extensive osseous destruction of the proximal radius (R) and ulna (U). Deformity of the forearm was apparent. There was marked periosteal reaction involving the distal humerus (black arrows, Figures 2a and 2b). A needle fragment projected over the antecubital space on both radiographs (red arrow, Figures 2a and 2b). These findings indicated the presence of osteomyelitis and septic arthritis. The needle fragment suggested drug abuse as the likely etiology.

This patient had a 2-year history of intravenous (IV) drug abuse. She initially noticed an open wound on her elbow about 6 months prior to presentation. As the wound worsened, she developed increasing pain, numbness, and weakness in her forearm and hand. Physical examination revealed a markedly contracted forearm. There was a large, deep ulcer at the lateral aspect of the elbow and proximal forearm, with exposed bone and surrounding necrotic tissue. Motor function was limited to minimal movement of the thumb and index finger, and there was complete loss of sensation in an ulnar distribution. A deep tissue culture grew methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and a bone biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of osteomyelitis. The patient was treated with antibiotics but ultimately required transhumeral amputation.

Intravenous drug users are at risk for soft tissue and bone complications, including ulcer, abscess, septic bursitis, tenosynovitis, cellulitis, necrotizing fasciitis, septic arthritis, and osteomyelitis.1 Osteomyelitis can arise from direct inoculation, hematogenous spread, or, as was the case in this patient, secondary to seeding from a contiguous soft tissue infection.2 Unlike hematogenous osteomyelitis, contiguous focus osteomyelitis is often polymicrobial.

Radiographs are not sensitive for osteomyelitis, particularly early in the process, but may reveal loss of soft tissue planes prior to the development of focal osteopenia and osseous destruction.3 In this case, the diagnosis could be made through radiography given the marked osseous destruction, periosteal reaction, and soft tissue ulceration. However, in presentations in which there is a continued clinical suspicion for osteomyelitis despite normal or inconclusive radiographs, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast is the preferred examination for further evaluation. While both contrast and noncontrast-enhanced MRI may show the bone marrow edema related to osteomyelitis, contrast is helpful in evaluating for soft tissue abscesses and in determining if there is an adequate blood supply for IV treatment to be effective. An alternative exam to MRI would be nuclear scintigraphy (a tagged, white blood cell scan and/or a three-phase bone scan).

Later in the disease course, periosteal bone reaction and sclerotic reactive bone formation can be seen. A sequestrum forms when there is complete resorption of the bone adjacent to a devitalized segment of infected bone, leaving the isolated devitalized segment to function as a nidus for continued infection.3

Dr Spivey is a resident in the department of radiology at New York Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. Dr Bartolotta is an assistant professor of radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City and assistant attending radiologist at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Dr Hentel is an associate professor of clinical radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. He is also chief of emergency/musculoskeletal imaging and executive vice-chairman for the department of radiology at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center; and associate editor, imaging, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.