Background

In practiced hands, ultrasound is more sensitive than chest X-ray in evaluating patients with suspected pneumothorax. Due to its portability, this modality can rapidly identify pathology and facilitate prompt intervention in a decompensating patient. This article reviews the proper techniques for evaluating patients for pneumothorax as well as the classic signs indicative of this condition.

Performing the Scan

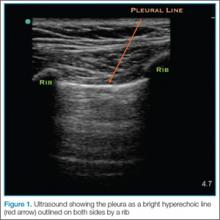

The probe also should be oriented as perpendicular to the chest wall as possible, which will make the pleura appear brighter. Once this view is achieved, the clinician can evaluate for evidence of lung sliding. Since air in pneumothorax rises to the least dependent portion of the chest, this is the area that should be evaluated. In the supine patient, the probe is placed on the anterior chest wall in the second intercostal space, midclavicular line. A high-frequency linear probe is best for evaluating pneumothorax and should be positioned with the indicator marker toward the head. The clinician will need to adjust the probe to visualize the pleura, which will appear as a bright hyperechoic line outlined on both sides by a rib with shadowing beneath (Figure 1).

Identifying PathologyLung Siding and Comet-Tail Artifacts

The appearance of lung sliding or a comet-tail artifact on the ultrasound confirms the lung is inflated. Lung sliding has been described as a shimmering appearance of the pleura, or like tiny ants marching on a string. The pleura will seem to slide back and forth as the patient breathes. Comet tails, vertical artifacts originating from the pleura, may be visible on ultrasound, also proving the lung is inflated (Figure 2).

The Lung Point

By continuing to scan laterally down the chest, the clinician may encounter the “lung point”—the junction between the normally inflated lung and pneumothorax. This point moves with respiration, and if visualized, confirms pneumothorax.

Motion Mode

Since lung sliding is sometimes challenging to visualize, using the motion mode (M-mode) on ultrasound can help to confirm findings. The M-mode takes a single line of echoes from the two-dimensional image and plots it against time. (The manner in which the image is produced may be thought of as a graph, with the x-axis representing time and the y-axis the depth.) When using M-mode, the screen will vary in appearance depending on the type of ultrasound being used. While performing the ultrasound, it is important to always keep the probe as still as possible to identify independent motion at the pleura.

Sand-on-the-Beach Sign

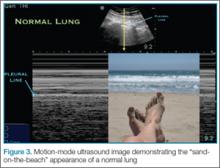

In a normal lung, M-mode images are often described as having a “sand-on-the-beach” appearance (Figure 3). As a normal lung inflates, the motion of the lung changes the brightness of the echoes that return to the machine, creating a speckled appearance like grains of sand beneath the bright pleural line. The soft tissues above the pleural line do not vary with time and thus have a linear appearance.

Barcode or Stratosphere Sign

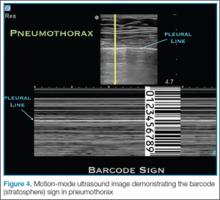

In pneumothorax, however, the granular sand appearance is absent. Instead, the M-mode shows a linear pattern below the pleural line. This pattern is described as the “barcode sign” or “stratosphere sign” (Figure 4).

Pitfalls

There are several pitfalls that can limit the ability to correctly diagnose a pneumothorax. The presence of scarring and adhesions may cause the patient to develop loculated air collections. If one evaluates only the anterior chest, air trapped in another location may be missed. The clinician should also be mindful of the presence of bullae as the appearance of sliding may be diminished in patients with bullous disease. Using the M-mode in these cases may help to identify inflated lung in patients with limited movement at the pleural line.

Furthermore, since it is easy to confuse a bright layer of fascia with the pleura, the clinician should always make sure to identify landmarks. In some cases of pneumothorax, subcutaneous air may obscure the pleura. The ribs should always be identified to ensure one is looking at the pleural line.

Although absence of lung sliding can suggest pneumothorax, other conditions, such as severe consolidation, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and mainstem intubation, can give a similar appearance. Remember, visualization of the lung point is pathnognomic for pneumothorax.

Conclusion

Pneumothorax is a medical emergency requiring immediate diagnosis and treatment. Patients presenting with suspected pneumothorax can be assessed quickly through bedside ultrasound. Once visualization of the pleura is established, the lung may be assessed for the presence or absence of normal lung sliding and comet-tail artifacts. The M-mode setting further enhances visualization and aids in the diagnosis of pneumothorax.